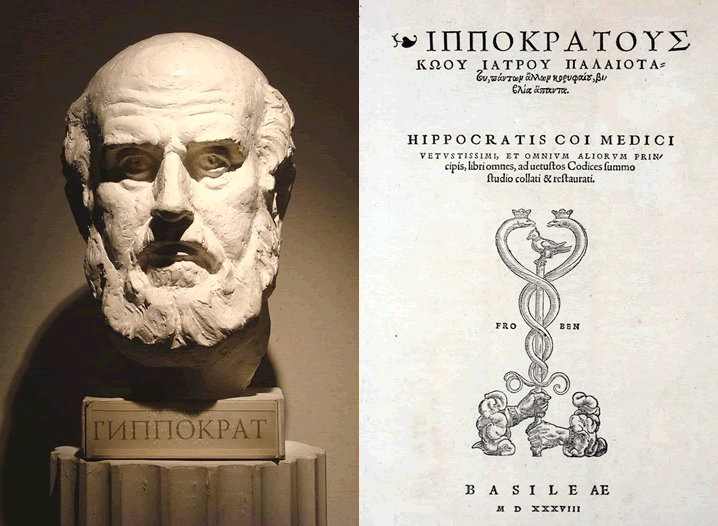

Hippocrates of Cos or Hippokrates of Kos

(Greek: Ιπποκράτης; Hippokrates; c. 460 BC – c. 370 BC) was an ancient Greek physician of the Age of Pericles (Classical Greece), and is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of medicine. He is referred to as the father of western medicine in recognition of his lasting contributions to the field as the founder of the Hippocratic School of Medicine. This intellectual school revolutionized medicine in ancient Greece, establishing it as a discipline distinct from other fields that it had traditionally been associated with (notably theurgy and philosophy), thus establishing medicine as a profession.

However, the achievements of the writers of the Corpus, the practitioners of Hippocratic medicine, and the actions of Hippocrates himself are often commingled; thus very little is known about what Hippocrates actually thought, wrote, and did. Hippocrates is commonly portrayed as the paragon of the ancient physician, credited with coining the Hippocratic Oath, still relevant and in use today. He is also credited with greatly advancing the systematic study of clinical medicine, summing up the medical knowledge of previous schools, and prescribing practices for physicians through the Hippocratic Corpus and other works.

Biography

Historians agree that Hippocrates was born around the year 460 BC on the Greek island of Cos; and became a famous ambassador for medicine against the strong opposing infrastructure of Greece. For this opposition he endured a twenty-year prison sentence during which he wrote well known medical works such as The Complicated Body, encompassing many of the things we know to be true today. Other biographical information, however, is likely to be untrue.

Soranus of Ephesus, a 2nd-century Greek gynecologist, was Hippocrates’ first biographer and is the source of most personal information about him. Information about Hippocrates can also be found in the writings of Aristotle, which date from the 4th century BC, in the Suda of the 10th century AD, and in the works of John Tzetzes, which date from the 12th century AD.

Soranus wrote that Hippocrates’ father was Heraclides, a physician, and his mother was Praxitela, daughter of Tizane. The two sons of Hippocrates, Thessalus and Draco, and his son-in-law, Polybus, were his students. According to Galen, a later physician, Polybus was Hippocrates’ true successor, while Thessalus and Draco each had a son named Hippocrates.

Soranus said that Hippocrates learned medicine from his father and grandfather, and studied other subjects with Democritus and Gorgias. Hippocrates was probably trained at the Asklepieion of Kos, and took lessons from the Thracian physician Herodicus of Selymbria. Plato mentions Hippocrates in two of his dialogues: Protagoras, where Plato describes Hippocrates as “Hippocrates of Kos, the Asclepiad,” and Phaedrus, where Plato suggests that “Hippocrates the Asclepiad” thought that a complete knowledge of the nature of the body was necessary for medicine. Hippocrates taught and practiced medicine throughout his life, traveling at least as far as Thessaly, Thrace, and the Sea of Marmara. Several different accounts of his death exist. He died, probably in Larissa, at the age of 85 to 90.

Hippocratic theory

Hippocrates is credited with being the first person to believe that diseases were caused naturally, not because of superstition and gods. Hippocrates was credited by the disciples of Pythagoras of allying philosophy and medicine. He separated the discipline of medicine from religion, believing and arguing that disease was not a punishment inflicted by the gods but rather the product of environmental factors, diet, and living habits. Indeed there is not a single mention of a mystical illness in the entirety of the Hippocratic Corpus. However, Hippocrates did work with many convictions that were based on what is now known to be incorrect anatomy and physiology, such as Humorism.

Ancient Greek schools of medicine were split (into the Knidian and Koan) on how to deal with disease. The Knidian School of medicine focused on diagnosis. Medicine at the time of Hippocrates knew almost nothing of human anatomy and physiology because of the Greek taboo forbidding the dissection of humans. The Knidian School consequently failed to distinguish when one disease caused many possible series of symptoms. The Hippocratic School or Koan School achieved greater success by applying general diagnoses and passive treatments. Its focus was on patient care and prognosis, not diagnosis. It could effectively treat diseases and allowed for a great development in clinical practice.

Crisis

Another important concept in Hippocratic medicine was that of a crisis, a point in the progression of disease at which either the illness would begin to triumph and the patient would succumb to death, or the opposite would occur and natural processes would make the patient recover. After a crisis, a relapse might follow, and then another deciding crisis. According to this doctrine, crises tend to occur on critical days, which were supposed to be a fixed time after the contraction of a disease. If a crisis occurred on a day far from a critical day, a relapse might be expected.

Hippocratic medicine was humble and passive. The therapeutic approach was based on “the healing power of nature” (“vis medicatrix naturae” in Latin). According to this doctrine, the body contains within itself the power to re-balance the four humours and heal itself (physis). Hippocratic therapy focused on simply easing this natural process. To this end, Hippocrates believed “rest and immobilization [were] of capital importance.” In general, the Hippocratic medicine was very kind to the patient; treatment was gentle, and emphasized keeping the patient clean and sterile. For example, only clean water or wine were ever used on wounds, though “dry” treatment was preferable.

Hippocrates was reluctant to administer drugs and engage in specialized treatment that might prove to be wrongly chosen; generalized therapy followed a generalized diagnosis. However, potent drugs were used on certain occasions. This passive approach was very successful in treating relatively simple ailments such as broken bones which required traction to stretch the skeletal system and relieve pressure on the injured area. The Hippocratic bench and other devices were used to this end.

One of the strengths of Hippocratic medicine was its emphasis on prognosis. At Hippocrates’ time, medicinal therapy was quite immature, and often the best thing that physicians could do was to evaluate an illness and predict its likely progression based upon data collected in detailed case histories.

Professionalism

Hippocratic medicine was notable for its strict professionalism, discipline, and rigorous practice. The Hippocratic work On the Physician recommends that physicians always be well-kempt, honest, calm, understanding, and serious. The Hippocratic physician paid careful attention to all aspects of his practice: he followed detailed specifications for, “lighting, personnel, instruments, positioning of the patient, and techniques of bandaging and splinting” in the ancient operating room.

The Hippocratic School gave importance to the clinical doctrines of observation and documentation. These doctrines dictate that physicians record their findings and their medicinal methods in a very clear and objective manner, so that these records may be passed down and employed by other physicians. Hippocrates made careful, regular note of many symptoms including complexion, pulse, fever, pains, movement, and excretions. He is said to have measured a patient’s pulse when taking a case history to know if the patient lied. Hippocrates extended clinical observations into family history and environment. “To him medicine owes the art of clinical inspection and observation.” For this reason, he may more properly be termed as the “Father of Medicine”.

Hippocratic Oath

The Hippocratic Oath, a seminal document on the ethics of medical practice, was attributed to Hippocrates in antiquity although new information shows it may have been written after his death. This is probably the most famous document of the Hippocratic Corpus. Recently the authenticity of the document’s author has come under scrutiny. While the Oath is rarely used in its original form today, it serves as a foundation for other, similar oaths and laws that define good medical practice and morals. Such derivatives are regularly taken today by medical graduates about to enter medical practice.

The “Oath”

By Apollo (the physician), by Asclepius (god of healing), by Hygeia (god of health), by Panacea (god of remedy), and all the gods and goddesses, together as witnesses, I hereby swear that I will carry out, inasmuch as I am able and true to my considered judgment, this oath and the ensuing duties:

- To hold my teacher in this art on a par with my parents. To make my teacher a partner in my livelihood to look after my teacher and financially share with her/him when s/he is in need. To consider him/her as a brother/sister along with his/her family. To teach his/her family the art of medicine, if they want to learn it, without tuition or any other conditions of service. To impart all the lessons necessary to practice medicine to my own sons and daughters, the sons and daughters of my teacher and to my own students, who have taken this oath-but to no one else.

- I will help the sick according to my skill and judgment, but never with an intent to do harm or injury to another.

- I will never administer poison to anyone-even when asked to do so. Nor will I ever suggest a way that others (even the patient) could do so. Similarly, I will never induce an abortion. Instead, I will keep holy my life and art.

- I will not engage in surgery–not even upon suffers from stone, but will withdraw in favor of others who do this work.

- Whoever I visit, rich or poor, I will concern myself with the well-being of the sick. I will commit no intentional misdeeds, nor any other harmful action such as engaging in sexual relations with my patients (regardless of their status).

- Whatever I hear or see in the course of my professional duties (or even outside the course of treatment) regarding my patients is strictly confidential and I will not allow it to be spread about. But instead, will hold these as holy secrets.

Now if I carry out this oath and not break its injunctions, may I enjoy a good life and may my reputation be pure and honored for all generations. But if I fail and break this oath, then may the opposite befall me.

Within this oath are both a moral code for the profession of medicine and the outlines of a system of accreditation for new physicians via an apprenticeship. These two functions went a long way to establishing medicine as a profession that ordinary people could trust.